Several large U.S. corporations have recently announced that they are planning to merge with foreign companies and move their corporate headquarters to a low tax country such as Ireland or Great Britain. The Obama Administration proposes to disallow such tax inversions by requiring that after such a merger at least 50% of the stock of the new company would have to be foreign owned. Such a regulatory fix is unlikely to solve a much more fundamental problem.

The Tax Foundation has just published a new study, “Tax Reform in the UK Reversed the Tide of Corporate Tax Inversions,” describing a similar situation in Great Britain just a few years ago and what was done to reverse it. Basically GB took two actions:

The Tax Foundation has just published a new study, “Tax Reform in the UK Reversed the Tide of Corporate Tax Inversions,” describing a similar situation in Great Britain just a few years ago and what was done to reverse it. Basically GB took two actions:

- Implementing a territorial tax system where profits are only taxed in the country where they are earned, and

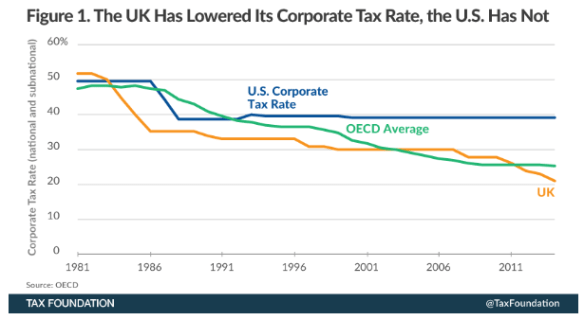

- Lowering the corporate tax rate from 28% in 2010 to 21% in 2014 and 20% in 2015. The GB rate had already been somewhat lower than the U.S. rate since the early nineteen-eighties.

These two changes in the corporate tax code have had a dramatic effect. First of all, the number of corporations in GB has been increasing steadily. By 2017 GB is likely to overtake the U.S. in total number of corporations.

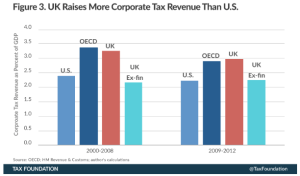

Secondly, GB actually raises more corporate tax revenue than the U.S. and has been doing so for some years. It should be clear from this discussion that the U.S. should significantly lower its corporate tax rate.

Secondly, GB actually raises more corporate tax revenue than the U.S. and has been doing so for some years. It should be clear from this discussion that the U.S. should significantly lower its corporate tax rate.

The biggest problem in doing this is public opinion. The organization Wallet Hub has just published its “2014 Tax Fairness Survey” which shows that only 10% of the population believes that taxes should be higher on wages than on investment income, whereas 33% thinks the reverse. An equal tax rate on both is preferred by 57% of respondents.

The biggest problem in doing this is public opinion. The organization Wallet Hub has just published its “2014 Tax Fairness Survey” which shows that only 10% of the population believes that taxes should be higher on wages than on investment income, whereas 33% thinks the reverse. An equal tax rate on both is preferred by 57% of respondents.

This will make it politically difficult, for example, for the U.S. to match GB’s 20% maximum rate on corporations since even middle class U.S. taxpayers pay a tax rate of 25% or higher. However it might be possible to abolish the corporate tax altogether if dividends and capital gains were then taxed at the same rate as wage income.

This will make it politically difficult, for example, for the U.S. to match GB’s 20% maximum rate on corporations since even middle class U.S. taxpayers pay a tax rate of 25% or higher. However it might be possible to abolish the corporate tax altogether if dividends and capital gains were then taxed at the same rate as wage income.

The most important thing, however, is to significantly lower the corporate tax rate, one way or the other, in order to incentivize U.S. multinational corporations to keep more of their business and profits in the U.S.