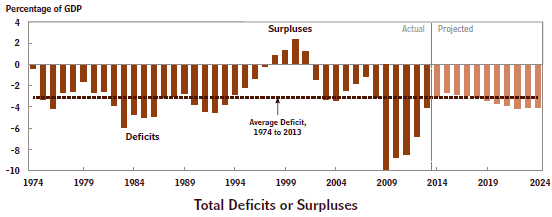

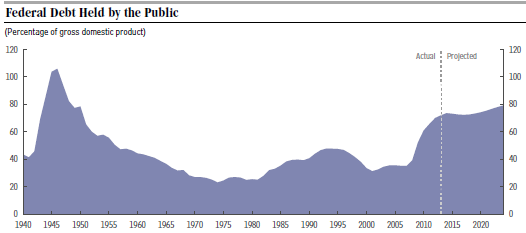

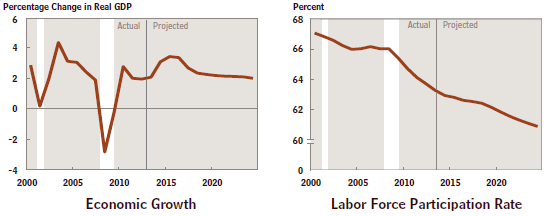

Last month the Congressional Budget Office issued the report “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2014 to 2024”, giving an updated prediction on economic performance. It predicts continued slow growth of GDP leveling off in the next few years at a rate of about 2.2% per year. The public debt (on which we pay interest) will be 74% of GDP this year and increase to 79% of GDP by 2024. Federal revenues will grow this year to 17.5% of GDP while federal spending will be 20.5% of GDP. The problem is that the gap between revenue and spending will get worse as indicated by the chart below.

CBO estimates that interest rates on three month Treasury bills will rise from 0.1% today to 3.7% in 2018, and higher in subsequent years, which means that interest payments on our public debt will increase dramatically as shown in the chart below. Inflation is predicted to average about 2% over this time period. Unemployment will slowly drop to 5.8% in 2017 and not reach 5.5% until 2024.

CBO estimates that interest rates on three month Treasury bills will rise from 0.1% today to 3.7% in 2018, and higher in subsequent years, which means that interest payments on our public debt will increase dramatically as shown in the chart below. Inflation is predicted to average about 2% over this time period. Unemployment will slowly drop to 5.8% in 2017 and not reach 5.5% until 2024.

In an article two days ago, an economics reporter for the New York Times, Floyd Norris, writes that this is “A Dire Economic Forecast Based on New Assumptions”. Mr. Floyd argues that it is unlikely that we will continue to have both anemic growth and high interest rates at the same time. Of course, if the economy does grow more quickly, then government revenues will also grow faster which will slow down the growth of the debt. But CBO predicts that our recovery from the Great Recession will continue to be tortuously slow.

In an article two days ago, an economics reporter for the New York Times, Floyd Norris, writes that this is “A Dire Economic Forecast Based on New Assumptions”. Mr. Floyd argues that it is unlikely that we will continue to have both anemic growth and high interest rates at the same time. Of course, if the economy does grow more quickly, then government revenues will also grow faster which will slow down the growth of the debt. But CBO predicts that our recovery from the Great Recession will continue to be tortuously slow.

The problem is that when interest rates do go up, as they will sooner or later, interest payment on the national debt will rise quickly, as shown in the CBO chart. This is going to happen and will be unpleasant to deal with. Are we going to have slow growth in the meantime, with high unemployment along with it, and then also have expensive debt payment later? This is indeed a pessimistic prospect!

We have a continuum of choices:

- Do nothing until the big crunch hits in a few years (like Greece)

- Cut spending dramatically, including for entitlements (politically infeasible)

- Raise taxes dramatically (also politically infeasible)

- Both cut spending and raise taxes (perhaps doable as we get closer to the big crunch)

- Grow the economy faster which would both lower unemployment and raise revenue

I know what my choice is, how about you?